The goal of investing in the stock market is to purchase equities that appreciate in value. When trying to determine which stocks to buy, many investors rely on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) to help determine an equity’s fair value.

The efficient market hypothesis (also known as the efficient market theory) isn’t followed by all, as the principles behind it are challenged by those who believe the EMH is a misrepresentation of how financial markets operate.

With this in mind, we’ll be taking a deep dive into what exactly the efficient market hypothesis is, the arguments for and against it, and how investors can use the efficient market hypothesis to make better investment decisions.

Understanding the Efficient Market Hypothesis

In simple terms, the efficient market hypothesis states that financial markets are 100% efficient in pricing assets. This means a company’s current value takes into account all available news, earnings reports, and other related information.

When a new piece of information comes out (for example, signing a new customer, expanding into a new market, or incurring higher than expected costs), the stock price will move upwards or downwards to reflect the new value of the company.

Those who believe in the efficient market hypothesis then also believe that outperforming stock market indices is impossible, as all market participants are making decisions based on the same information and that no inefficiencies exist within markets.

History of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient markets hypothesis was born in the early 1900s by mathematician Louis Bachelier, who researched the randomness of financial markets.

Bachelier was on the right track regarding how and why stock prices move. However, the person accredited for creating the efficient market hypothesis, as we understand it today, is American economist Eugene Fama.

In the 1970s, Mr. Fama published a book titled “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work,” which stated that current stock prices reflect all available and relevant information about a company.

Fama believed that outperforming financial markets through either fundamental or technical analysis was impossible.

Even if investors picked a stock that saw its share price rise dramatically in a short period of time, in the long term, asset prices would eventually revert back to their fair market value – meaning no investor (including top fund managers or other professional investors) could not reliably beat the market.

The efficient market hypothesis has gained popularity since the 1970s, with different variations emerging from investors who argue both for and against the concept of true market efficiency.

The Three Variations of the Efficient Market Hypothesis

With the efficient market hypothesis being highly controversial and disputed, economists and investors alike worked to adjust the original work done by Eugene Fama, to help better explain price movements in stocks and overall market movements.

Currently, there are three variations of the efficient market theory:

Weak Form Efficiency

Those who accept the weak form of the efficient market hypothesis still believe that stock prices reflect all the current information of a company. However, when new information is released, it’s not immediately priced into a company’s valuation.

New information, such as a recent acquisition or a company’s latest earnings report, takes time to be accurately priced into an equities share price. Implying that market inefficiencies do exist, and prudent investors who utilize fundamental analysis to identify undervalued stocks have the opportunity to outperform markets consistently.

Additionally, weak form efficiency also supports the belief that past price performance provides no indication of future prices (as future prices are solely influenced by the latest news related to a company). Or in other words, technical analysis provides no value to investors.

Semi Strong Form Efficiency

The semi strong form believes that no public information (new or old) will affect an asset’s price, as markets are quick to price in new developments of a company.

This makes it impossible to buy undervalued stocks or for equities to have inflated prices, as share prices reflect all relevant information.

However, developments of a company that is not publicly available make it possible for those with insider knowledge to generate excess returns in the long run.

Unfortunately, in this form, neither fundamental analysis, in-depth research, nor technical trading strategies will help investors outperform the index. Only having access to information that is not publicly available will help investors outperform.

Strong Form Efficiency

Neither public nor private information will help investors reliably outperform the broader financial market under the strong form efficiency variation.

There is no room for market timing strategies, asset bubbles, or even insider information in financial markets, as markets are 100% efficient in pricing assets.

Further, having perfectly priced assets leaves no room for investors or active managers to find under or overvalued equities to purchase. As such, the performance of actively managed funds and portfolios will fall far below the market average.

What Makes a Market More Efficient?

To understand what makes financial markets more efficient, imagine investing back in the 1900s before online banking was available and investors had to call their broker when placing a trade physically.

Additionally, financial websites, like Yahoo Finance or Edge Investments, didn’t yet exist, making it extremely difficult for investors to make decisions based on the most relevant and accurate information.

Today, investing has become much easier and more accessible. Online banking allows investors to buy and sell stocks with a click of a few buttons. Gaining access to current financial news or trends has never been easier.

In short, what makes markets more efficient is giving a higher number of market participants access to the most relevant and important information that is influencing financial markets. As information has become easier to obtain and the barriers to buying and selling stocks have been removed, markets inherently become more efficient in accurately pricing assets.

Can Markets Be Inefficient?

Answering the question of whether or not markets can be inefficient is perhaps best answered by using examples.

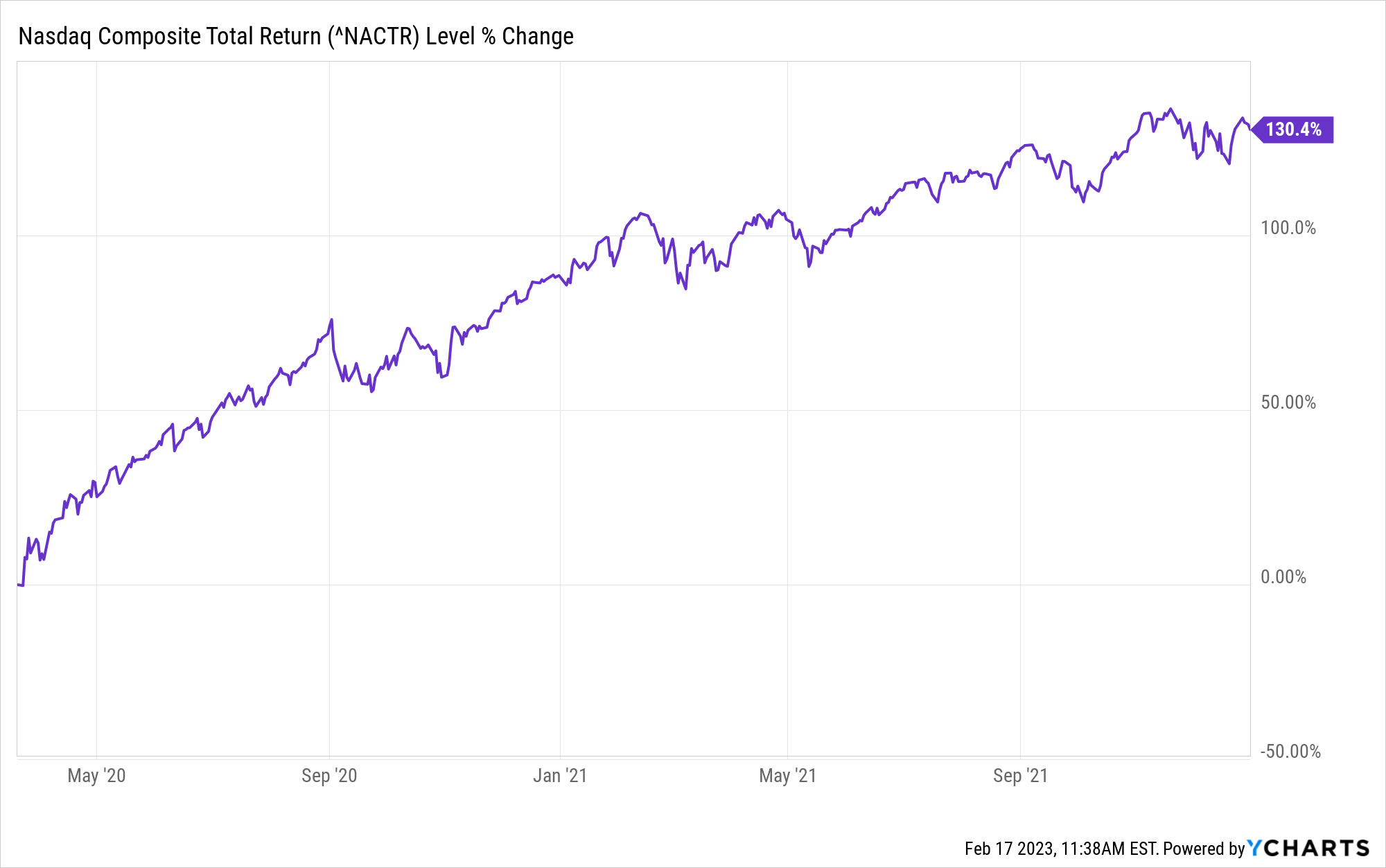

Most recently, investing during the pandemic created by COVID-19 has led many to reconsider whether or not markets are efficient. More specifically, when the pandemic first began, technology stocks soared in value, leading to the tech-heavy NASDAQ gaining 130% between March 2020 and December 2021 (see chart below).

However, while tech stocks were rising in value, the economy was struggling. Supply chains were backed-up, companies were laying off staff, and entire countries were deploying unprecedented levels of fiscal stimulus in an attempt to avoid a recession.

Were markets accurately pricing in a struggling economy and the devastating effects of a global pandemic?

Many would argue no. Markets failed to account for a slowing economy, the incoming rise in inflation, and backed-up supply chains.

So, if markets failed to efficiently price in the current economic problems that were caused by a global pandemic, then stock prices should then move downwards to reflect a less than favorable financial and economic environment.

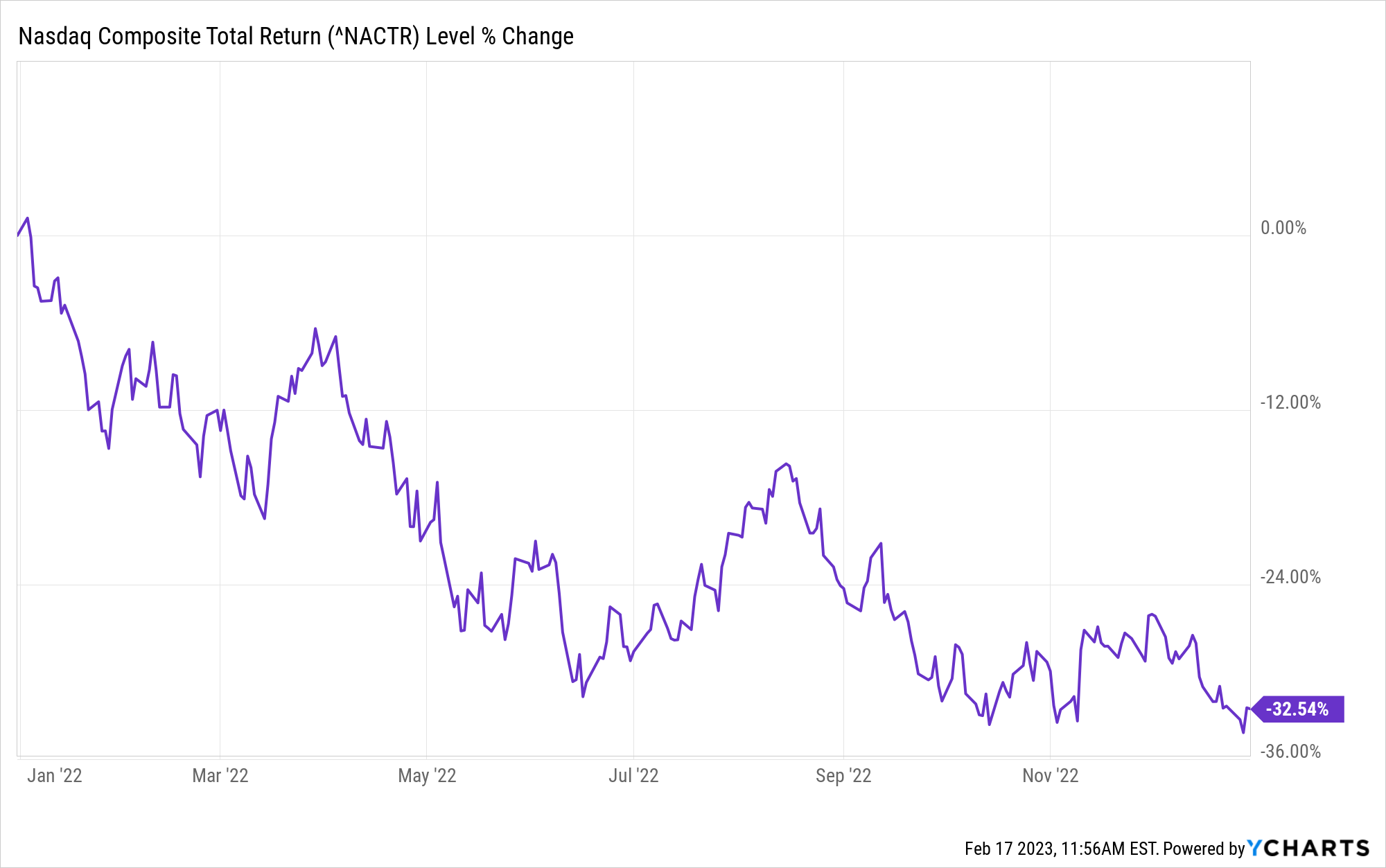

And in 2022, this is exactly what happened. The chart below shows the NASDAQ retreating by over 30% (with many individual companies watching their stock price drop by 90% or more), as investors began to realize the current economic problems would adversely affect the profits and growth of companies.

Nasdaq Composite Total Return, YChartsCOVID-19 and the effects of a global pandemic on financial markets is an excellent example of when markets were inefficient in pricing assets. Investors wrongly assumed that low-interest rates set by the Federal Reserve would remain that way forever and that large amounts of fiscal stimulus injected into the economy would not lead to the highest inflation seen in the last 40 years.

This mistake led to extreme swings in price movements, which is a market characteristic that shouldn’t and wouldn’t happen if financial markets were completely accurate in determining a company’s fair value.

Investors Who Consistently Outperformed Markets

Another example of markets being inefficient comes from famed investors who achieved outsized investment returns beyond what the benchmark index produced over an extended period of time.

Investors such as Warren Buffet, Peter Lynch, and Howard Marks prided themselves on identifying undervalued stocks which would produce investment returns that outpaced the average market return.

Many use the simple fact that some investors, who were able to achieve greater returns than others consistently, prove markets aren’t completely efficient at pricing assets.

Arguments For and Against the Efficient Market Hypothesis

Throughout history, there has been evidence to both support and disprove the efficient market hypothesis.

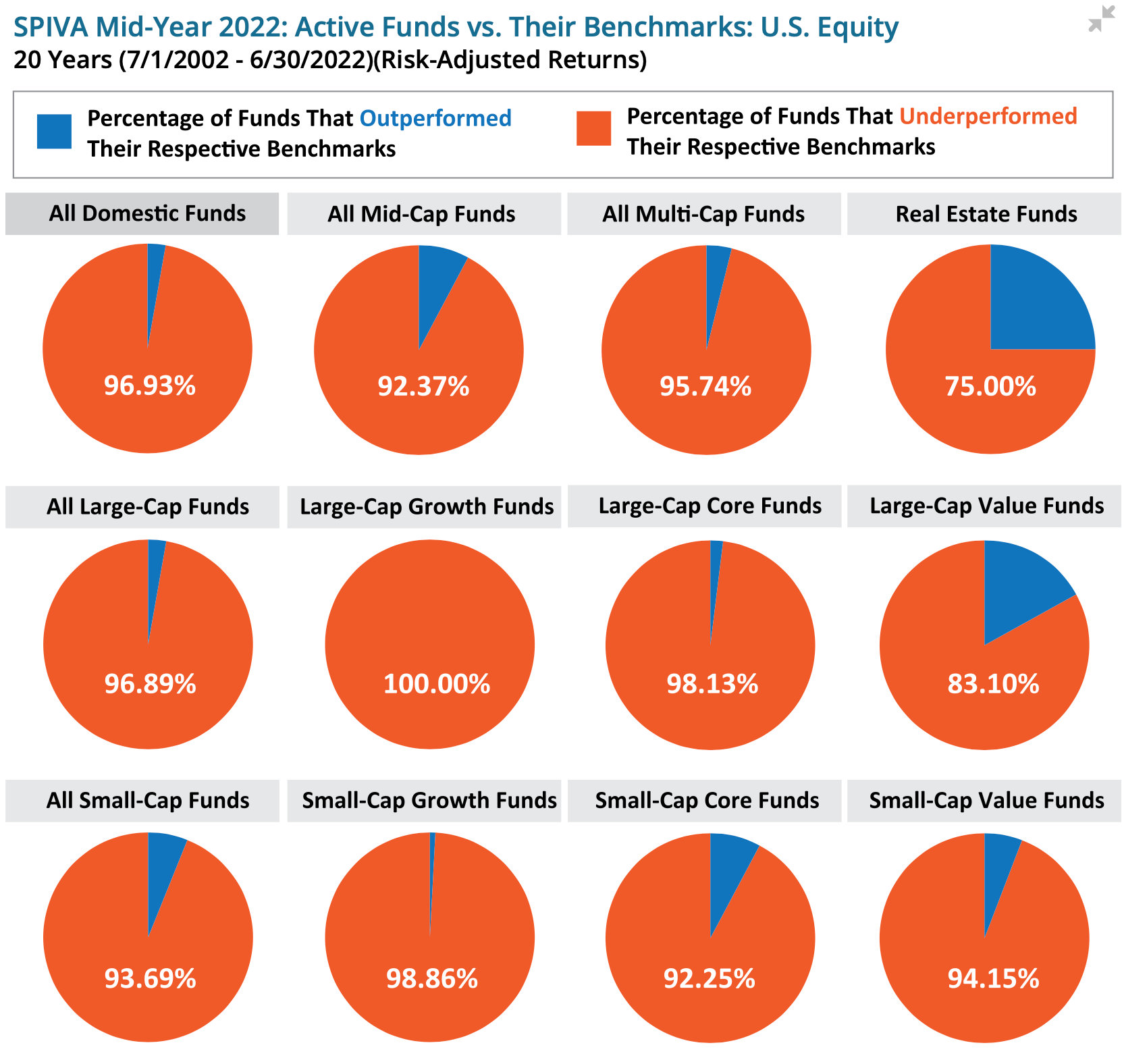

In support of the EMH, a recent report published by SPIVA showed over 80% of actively managed funds failed to outperform their respective benchmark over the last 15 years.

Further, the chart below shows (in orange) the amount of active managers who underperformed their respective benchmark, and (in blue) the funds which outperformed.

With the majority of asset classes showing over 90% of active managers failed to outperform the index in a 20-year time frame makes a compelling argument that the efficient market hypothesis is, in fact, true.

On the other end of the spectrum, those who discount the efficient market hypothesis point to the many crashes and bubbles that financial markets are known for producing. More specifically, the 2008 financial crisis, the more recent global pandemic, and even the flash crash of 2010 show that markets are not efficient in pricing assets.

Additionally, the fact that some investors (like those mentioned above) have been able to outperform the index consistently proves that opportunities exist to find individual companies which trade below their fair market value.

Wrapping Up

In truth, outperforming broad financial markets is an extremely difficult undertaking, and most of the time, markets are efficient in accurately pricing assets. With the modern financial world allowing for much-improved access to financial information and the ability to place trades faster and easier, it has led to markets becoming more efficient – and more difficult for investors to achieve a superior return when measured against an index.

However, this doesn’t mean that markets are always able to accurately digest current information and subsequently price assets efficiently. Financial bubbles do occur, and investors don’t make financial decisions based purely on information. Instead, investors are known for making emotional decisions with their money, leading to poor decision-making and inaccurately pricing assets.

Instead of blindly following the efficient market hypothesis or discounting the economic theory entirely, investors should accept that the EMH has its benefits and shortcomings much like any other investing strategy.

No, markets won’t be right all the time, though beating the index is an extremely rare accomplishment that most fail to achieve long term.

The importance of building a diversified portfolio containing both individual stocks and a benchmark index, as well as keeping an appropriate amount of cash on hand to capitalize on opportunities, is perhaps the most important takeaway for investors when analyzing the efficient market hypothesis.